Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Lexington, Kentucky is a wonderful place, and that’s getting to be a problem. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with the city: its urban amenities, thriving information economy, and unique local culture have brought in throngs of economic migrants from locales as exotic as Appalachia, Mexico, and the Rust Belt. The problem, rather, is that the city isn’t zoned to support this newfound attention.

Over the past five years, the city has grown by an estimated 18,000 residents, putting Lexington’s population at approximately 314,488. Lexington has nearly tripled in size since 1970 and the trend shows no signs of stopping, with an estimated 100,000 new residents arriving by 2030. Despite this growth, new development has largely lagged behind: despite the boom in new residents, the city has only permitted the construction of 6,021 new housing units over the past five years—not an awful ratio when compared to a San Francisco, but still putting us firmly on the path toward shortages. The lion’s share of this new development has taken the form of new single-family houses on the periphery of town.

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with single-family housing on the periphery of town. Yet in the case of Lexington, it’s suspect as a sustainable source of affordable housing. Lexington was the first American city to adopt an urban growth boundary (UGB), a now popular land-use regulation that limits outward urban expansion. As originally conceived, the UGB program isn’t such a bad idea: the city would simultaneously preserve nearby farmland and natural areas (especially important for Lexington, given our idyllic surrounding countryside) while easing restrictions on infill development.

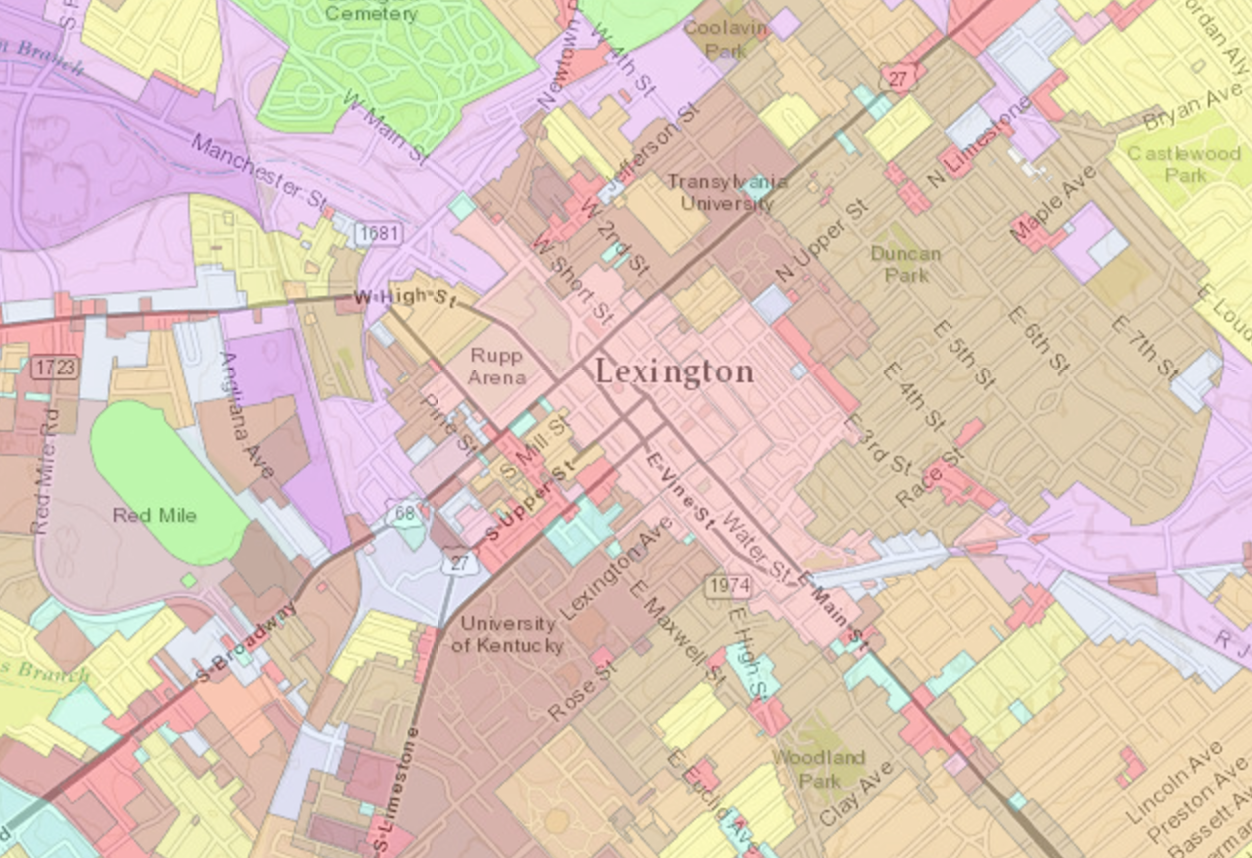

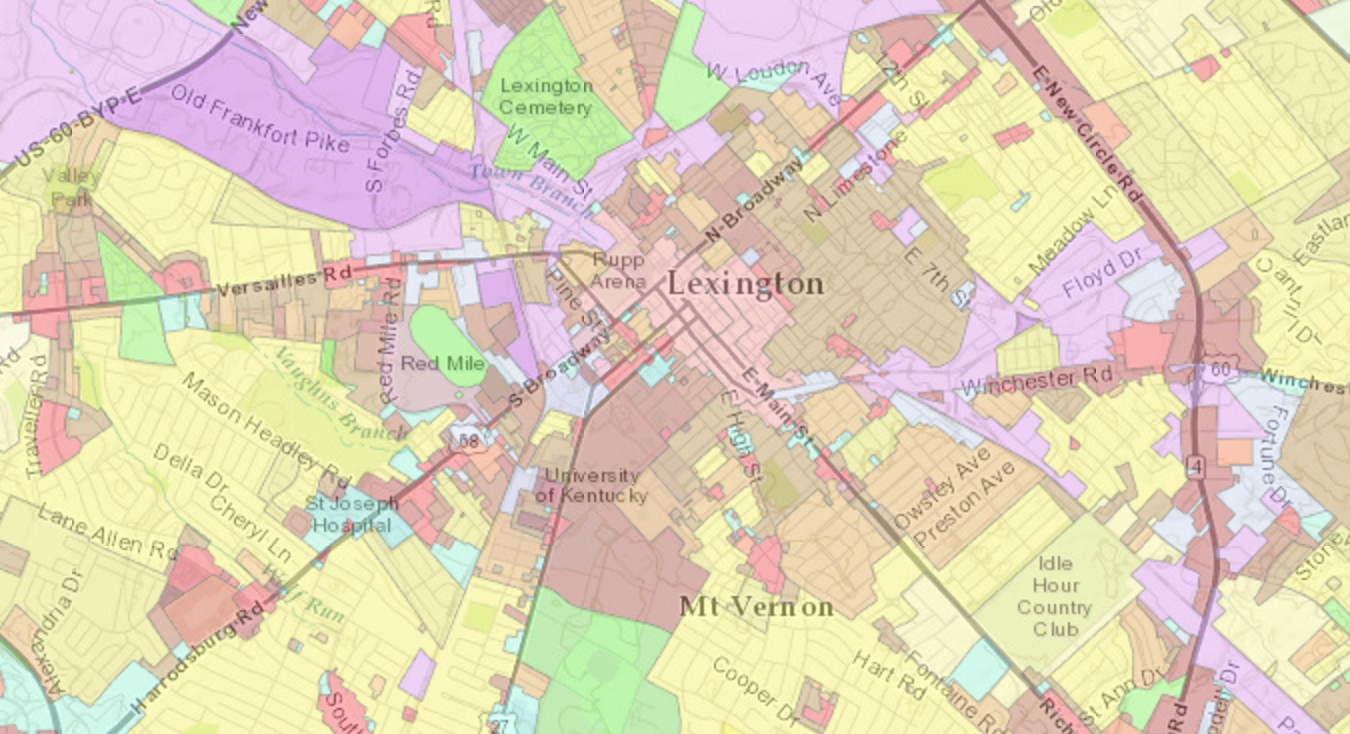

The trouble with Lexington is that the city has undertaken the former and ignored the latter. Much of the city is zoned exclusively for either agricultural residential—increasingly taking the form of affluent rural estates—or single-family residential. Even where higher densities are permitted, the tight restrictions on urban development that are a normal feature of Euclidian zoning are often present: unnecessary setbacks, surprisingly low maximum heights and lot coverage, and high minimum parking requirements. For all intents and purposes, Lexington’s zoning code criminalizes the kind of traditional urban development that is very much in vogue among young professionals buying home and condos.

The sad result of this booming demand and restrained supply has been to place enormous strain on Lexington’s existing urban neighborhoods. According to a recent investigation by the Lexington Herald-Leader, low-income residents in urban neighborhoods—most prominently, along North Limestone—are facing rising rents and property tax bills. It’s a trend that appears to be affecting many low- and middle-income urban and inner suburban neighborhoods around town; according to one report, the city has lost 28,000 affordable housing units since 2014 alone.

With the support of Councilman James Brown, the city is investigating ways to offer property tax relief to those most vulnerable to the squeeze, particularly low-income homeowners on fixed incomes. It’s an admirable effort to mitigate the damage done by decades of poor policy. Yet if policymakers continue to ignore the issues with the city’s zoning regime, this problem will only worsen. With this in mind, here are three policies that could help expand affordable housing in Lexington—without touching the UGB.

1. Permit Accessory Dwelling Units As Of Right in Residential Neighborhoods

In many of Lexington’s inner suburban neighborhoods, hidden among what look like single-family houses, one might find an underrated source of affordable housing: accessory dwelling units (ADUs), or additional small housing units tucked into the basements, garages, and attics of homes. A few have been added in recent years to Kenwick—a gentrifying neighborhood that is zoned for duplexes—and many remain as non-conforming uses in neighborhoods like Hollywood.

Accessory dwelling units were a common feature of American cities until the rise of Euclidian zoning and offer many benefits for renters, homeowners, and communities. For renters, they offer an affordable unit in a neighborhood that (for them) might otherwise be unaffordable. For homeowners, they offer an additional source of income. Alternatively, they are often used to house elderly relatives and support young adult children. For communities, they provide diversity without the unwanted unpredictability—homeowners, after all, have a vested interest in only permitting tenants who behave themselves.

Except in certain unusual circumstances—in duplex districts or on legally non-conforming lots—ADUs are not allowed in most of Lexington’s residential areas. This is a peculiar missed opportunity, as many similar uses—including servants’ quarters and guesthouses—are already allowed in residential districts. Permitting ADUs in residential districts offers an unobtrusive way to add new units of housing to Lexington’s existing desirable neighborhoods.

Lexington wouldn’t be alone in adopting to such a policy: Durango, Colorado—another college town with beautiful surroundings and a nasty housing crunch—recently launched a pilot program to explore how ADUs could be added to the city. Austin, Texas—another booming information economy hub—also recently eased restrictions on ADUs. While Durango and Austin are facing housing crunches even greater than Lexington’s, local policymakers should get out in front of the problem by exploring how other cities have reformed ADU regulation and start the process of reform today.

2. Convert Downtown Commercial Zones to Mixed-Use Zones

Cities are complex systems—they defy simple cause and effect explanations. Yet one contributing factor to the booming demand in communities in Northern Lexington may be that they are among the only neighborhoods offering traditional mixed-use urban form. As many have pointed out, Americans increasingly prefer dense, mixed-use urban neighborhoods to low-density, use-segregated suburbs. Under a liberal planning regime—consider Houston or much of Japan—uses and densities might change to accommodate this new demand. Yet under Lexington’s Euclidian zoning regime, potentially dynamic neighborhoods like Woodland, South Hill, and South Broadway are kept largely locked in time.

Consider the traditional neighborhood center: apartments and offices above street-level retail. Under the standard B-1 zone—and many of the city’s other business zones—such an arrangement is prohibited. Upzoning and permitting mixed uses in these districts could help expand the housing supply and provide new residents with options beyond the handful of existing urban neighborhoods. Take South Limestone, arguably one of Lexington’s most exciting streets (pictured above). To the right, at the intersection of S. Limestone and Avenue of Champions, sits a seven-story dormitory with street level commercial. It reflects booming demand for student housing for the area and could only be constructed thanks to the University of Kentucky’s peculiar zoning status. Now look to the left: squat two and three story buildings, all exclusively commercial, with many of the lots hosting surface parking. This bizarre contrast in use mixture and intensity illustrates the restrictiveness of the block’s current B-1 zoning. What might be dense blocks with hundreds of residential units for young professionals and students are instead preserved as they were built in the 1960s.

All across downtown and the inner suburbs of Lexington, one finds business districts that could be thriving mixed-use hubs—if only they were allowed (a few that come to mind: Southland Drive, the commercial district near Euclid Avenue and High Street, the various low-density developments between Virginia and Waller along Broadway, etc.). Lexington planners and policymakers have been forward thinking in permitting mixed-use developments in around town from time to time. Yet the level of discretionary review the current process requires raises compliance costs for developers and undermines the affordability of new developments—when they happen at all. By switching downtown business zones over to mixed-use zones and easing restrictions related to height, lot coverage, and setbacks, policymakers could expand options for downtown housing and reduce pressure on existing urban neighborhoods.

3. Eliminate Parking Requirements

Perhaps the lowest of the low-hanging fruit, Lexington policymakers should scrap parking requirements altogether. Lexington’s zoning ordinance is positively packed with them—you must build three parking spaces for every two apartments, two spaces for every duplex, one spaces for every two hundred feet of offices and restaurants, etc.—and they ultimately undermine Lexington’s efforts to flower into a leading American city. As has been documented by many studies, minimum parking requirements reduce affordability by raising the cost of development and undermine urban living by reducing densities and requiring auto-oriented development.

If our aim is to create more urban mixed-use neighborhoods in Lexington, it is absolutely essential that minimum parking requirements go. Under current requirements, a lovely fourplex in an R-3 would require at least six parking spots. Under current requirements, a 6,000 square foot café in a B-1 district nestled in a residential community would require at least 10 parking spots. These requirements may not seem like much, but in the world of small urban development—a world of modest lot sizes and tight budgets—these requirements can and do kill projects. For the purposes of affordable housing, the former case is most pernicious, as fewer small apartments and duplex means fewer affordable housing opportunities.

Aside from harming housing affordability, the damage that parking requirements cause to urban design can’t be overstated. Under current zoning, wonderful urban streets like South Mill Street (pictured above) are prohibited while monstrosities like the South Limestone McDonalds (pictured below) are effectively required. The impact on urban design may be greatest on Downtown, where any new large multifamily development would require a costly parking garage. This may be one reason why relatively few people live downtown—Lexington’s population center actually lies to the south, around the University of Kentucky. A lack of residents means fewer downtown restaurants and shops and less sidewalk activity, making it less attractive to prospective businesses. Removing these out-of-date restrictions would go a long way toward supporting downtown Lexington’s renaissance and expanding the housing supply.

Flipping through the city’s zoning ordinance, one might suspect that Lexington’s planners already know all this. They have, after all, spent the past few decades adding various exceptions: tradeoffs for bicycle parking, special exception districts, etc. While each individual exception to mandatory parking minimums may be wise, in the aggregate they form an incoherent mess that forces dependence on a land-use lawyer. Why not eliminate the mandated parking altogether?

—

In many ways, Lexington has the best kind of problem. Thousands of people want to live here, whether brought in by economic desperation in nearby Appalachia, a flourishing research university, and our growing 21st century economy. Yet as rising housing costs and rapid gentrification reveal, we desperately need more housing to support all the new Lexingtonians. If we don’t change zoning to reflect this, sprawl will merely leapfrog the UGB and residents who can’t afford rising rents will be forced out. Thus far, the debate over this challenge has been limited to whether or not we should expand the UGB. While the UGB is an important part of the discussion, this is a false dilemma. Three simple policies—permitting accessory dwelling units, expanding liberal mixed-use zoning, and eliminating parking requirements—could expand the supply of urban housing and ease the crunch on low-income residents.

I also live in Lexington, and the issues the writer points out are spot on–particularly the parking lots in downtown. I am, however, skeptical on the attribution of these issues to gentrification and affordability. For beginners, Lexington is faced with gentrification issues in part because our city leaders refused to even mention the term until a month ago (in the article linked by the author). This is not “bravery,” to which our author ascribes our council member’s actions, but neglect. I actually sat in on the last time these leaders attempted to mention the word (an informal sit-down with 10 or so area leaders), and to a person they all claimed that gentrification was not occuring in the city. This was in 2013.

More broadly, though, the focus on using zoning to make downtown more affordable seems off. For one, the city has inflated most of the urban real estate value by giving private developers somewhere around $800 milllion in various types of subsidies for high-end apartments, modern art hotels, and a pimped out convention center/basketball arena. They’ve surrounded those private developments with another hundred million+ dollars in urban upgrades (mainly, an urban bike trail that literally connects the subsidized private interests). Not only does this inflate the value of those urban holdings, and the near-urban holdings of smaller property owners like me (who lives 4 blocks off main in a house w/ a .20 acre lot), but it also serves to devalue the homes outside of the urban hip-zone–when the city focuses on procuring money and planning for a cool downtown, the inevitable byproduct is lack of thought and subsidies for the rest of the city’s neighborhoods.

A last note on Lexington: the author suggests that high-rise (or multi-family) apartment buildings belong in the inner city. In Lexington, like in other sprawled southern cities, dense apartment buildings are going up around town–it’s just on the urbanizing outer edges along our New Circle and Man O’War Roads, where costs are cheaper. The “1950s/2010s” image of a low-rise commercial building next to the University of Kentucky’s new dorm is sort of a trompe loeil here. For starters, the high-rise was not built just because of zoning, but mainly because the public-entity university, with a $2.2 billion budget, sold off development rights to its campus to a private contractor–hardly the “standard” development path of most privately-funded apartment complexes. The area is also not stuck in 1950s mode. One block behind the low-rise commercial building in that picture sits a six-story, private sector, student apartment that was build a decade ago. One block behind that, on Broadway, lies yet another high-rise apartment complex for students–with an entire bottom floor of commercial storefronts that have stood vacant since construction 5 years ago. Density is there–it’s just that residents can afford to buy nearby single-family homes with yards for way way way cheaper; apparently, they do not feel the need to be next to the city’s old downtown.

(And, of course, gentrification generally de-populates a city as cramped subdivided homes get purchased and turned back into single-family dwellings…yet another way that the impulses of the creative class put pressure on urban density and price inflation.)

Thanks for the feedback. I agree that many of the subsidies the city has been handing out to private developers are unethical and wasteful. The luxury hotel struck me as especially awful. The Legacy Trail was poorly managed, but at least it is a public amenity.

Sorry….I neglected to get back to this earlier.

Gentrification is about disinvestment, depopulation, and then the construction of new amenities (private and public). I think you are focusing just on the 3rd part.

I would think that the city spending $100 million to put 2 bike trails within 1/2 mile of my house has immensely increased the value of my home. How would it not? So, too, has the city’s “fighting fund” of $2 million/year for high-tech workers to locate here–imagined, usually, as a population of urban creatives looking for in-town homes, ideally located nearby amenities like an art hotel (also 1/2 mile from my home), bars, bike trails, and the home of UK’s nationally known basketball team.

And if these things don’t directly effect my home value–and I and realtors and our mayor would state that they do effect value positively (along with the 2 private developers who just got $4 million TIF subsidies to help their new construction at the terminus of one of the new bike trails)– I would also think that these subsidies also influence where small-scale private business gets located. These subsidies attract media focus, which attracts private capital.

You describe these subsidies as “rising demand” and contrast that with the city throwing out trash into the streets. I get the humor, but this is more or less what the gentrifying northside experienced from the city before infill by a community of capitalized newcomers (people like me). In others, stages 1 and 2 of gentrification. It wasn’t until the city experienced an onslaught of private capital (demand) that the city began to throw subsidies into the area. (In “street upgrades,” are you referencing the portions of 2 streets that were made 2-way, the Main Street “beautification” project, or a couple of ped bump-outs that have appeared nearby gentrification hotspots like 6th/Lime? As a resident, I can say pretty safely that these have had little to no impact on my property values.)

I don’t buy your distinction between the “difficulty” of non-urban construction and urban construction. The process for building downtown has been just as fraught with difficulty as the non-downtown projects. This is why CM Steve Kay spent 4 years developing downtown development guidelines: it was too costly for developers. (And, to be clear, downtown has de-densified between 200 and 2010. If “density” is happening here, it’s just catch-up. There are several areas outside of downtown/UK that are way more dense….and this is exactly what gentrification theory predicts.)

I’ve got more to say, but I’m late for beers at Blue Stallion. 🙂

Allright….I’m back from Blue Stallion. The last point I want to make concerns your “Urban Growth Boundary” drives gentrification more than $1 billion in urban subsidies thesis.

The city has embarked on an “affordable housing trust fund.” The fund, as I gather you know, was established in 2014 (an election year, surprise-surprise) and gets around $2.2 million each year. This sounds great–progress!–but it is (1) 85% under what it needs to be funded at (according to the city’s own studies), and (2) less than the “property development rights” fund, established in 2000, which gets $2.5 million per year. This fund goes to paying wealthy large property owners on the outskirts of the city for the “development rights” to their property. So…a 15 year headstart for wealthy landowners, and an approximate $300,000/year advantage in assuring their interests get met over those of the vast, vast, vastly more numerous people needing help with affordable housing. This outside-urban-growth-boundary subsidy is in addition to the hidden subsidies for, say, horse racing economies like investments made on our only two urban trails, both of which go to horse country rather than residential/commercial areas–and the only finished trail of these goes to our state-subsidized Kentucky Horse Park, recipient of over $100 million in subsidies to prepare for 2010’s World Equestrian Games.

Maybe instead of zoning/planning/urban growth boundary issues…the problem is much more simple: we subsidize the already wealthy (both urban and rural), such that the city’s growth follows the billion dollars plus in city development that, eveno our mayor has said, connects a “historic” (massively subsidized) downtown to a historic (massively subsidized) horse country.

I’d imagine this is the case in Portland, too–subsidies to wealthy and connected developers to follow their below-value real estate purchases–if CHuck were to live there and study it more. Zoning is an easy bogey-man; following the money, though, shows why development travels where it does.

Your picture of South Limestone is disingenuous at best. A block to the left is multi-level condos/apartments with vacancies and commercials on first floor. Down the street is more of the same, but with commercial vacancies. Downtown is getting huge injections of apartments and condos and is building up. The south hill down towards the campus doesn’t need to go up- that will just kill its atmosphere. There isn’t parking there for more either. And taking a reasonable parking situation in Lexington and turning it into a nightmare for no reason other than to try to jam more students down town is the opposite of running a city properly. People come to live here from places like DC because they don’t want to deal with that kind of density. Along the same note, downtown life is unique here and most would rather living in an apartment/condo in the suburbs with some grass and personal lots. And those have been going up everywhere. And those people want to come downtown and have parking to do so. The McDonalds mentioned may stick out like a sore thumb with its lot never full, but there isn’t the density to deal with more, nor would there be parking if there was. Taking a picture of the college corner of town mid-summer isn’t being fair. Not taking into account that there’s enough vacancies in that area that prevent developers from bothering with multi-use buildings, when there isn’t enough demand for people live atop a loud college bar.

If you’re worried about gentrifying North Limestone, pointing out that there’s not enough people cramped in across the street from freshman housing without parking isn’t a winning argument.

To summarize: “Legally mandate my preferred living arrangement.”

No.

To summarize “If we turn Lexington into a ghetto, my guilt will be purged!”

Maybe you should get an actual job before you continue academia.

“Maybe you should get an actual job before you continue academia.”

people go into academia so they can avoid actually living in the real world.