Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Recently I’ve been seeing a lot of articles about slums (the NYT on Gurgaon, India, and the Guardian on Cairo), and inevitably the phrase “free market” gets thrown around. And as it should – so-called “slums” often have very minimal active governance, and as a result they often have very dynamic economies and upwardly mobile citizens (something even the New York Times and Guardian, two very liberal papers, recognize).

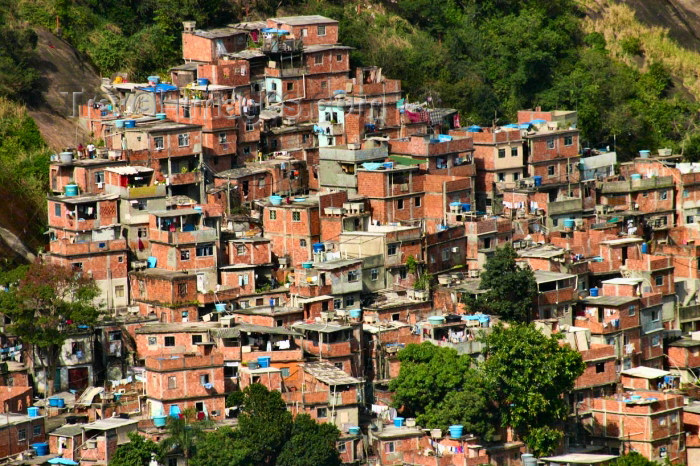

But it’s lazy to equate them with the free market, and unfortunately I see a lot of people doing that. One problem with slums, from a free market point of view, is that only certain investments are secure. People and their houses (well, at least the owner-occupied ones) are the safest, especially in democracies like Brazil and India. Though of course there are stories of people’s homes in slums being demolished or taken by the government without compensation, it’s my understanding that this is becoming rarer as slum dwellers grow in number and political power. Residents are likely to get titles in some Hernando de Soto-inspired regularization scheme, so people invest in their homes. Residential areas harden as sheet metal turns into bricks, houses get proper roofs, and we start to see two- and three-story structures.

Infrastructure, however, is another story. While many newspapers I think generally exaggerate the lack of services (I refuse to believe the Times’ assertion, for example, that Gurgaon only has employer-funded mass transit – there must certainly be share taxi/small bus services, or at least motortaxis), there does appear to be a real lack. The poorer areas often have open sewers, and running water in homes is rare. Many critics take this as evidence that infrastructure – paved roads, mass transit, electricity, waste collection, water – will not be adequately provided for in a free market, which is a reasonable thing to believe if you think slums are the free market incarnate.

But they are not. It may appear that way because the government isn’t helping, but bribes are still being taken and certain regulations are sometimes enforced, especially against high-profile things like infrastructure. Take, for example, the issue of electricity. Normally what slum dwellers do is hook up their homes and businesses to small generators, which is very inefficient, expensive, and polluting. (Oftentimes they also steal from the government, but obviously you can’t blame that on the free market.) A generator is small and doesn’t attract much attention, and it’s difficult to extract bribes from them because they are distributed among the population – in other words, people get away with them. Real power plants, however, even though they are more beneficial to society, are much more likely to come to the government’s attention, and thus are too risky for entrepreneurs to invest in. Given their prominence, the government will ask the operators for a bribe if they’re lucky, but more likely will just shut the power plant down for not complying with whatever draconian regulations are forcing people to opt out of the “legal” world in the first place.

And though consumers would benefit from these illegal power plants (or sewers, or water pipelines, or railroads) just as they benefit from their illegal homes, consumers are often hostile to the businessmen they are served by (think about the wild anti-rail sentiment of turn-of-the-century urbanites, or the anti-ISP sentiment that we have today), so they aren’t likely to come to their aid when the state tries to seize their property. Their customers might in fact be the ones with pitchforks at the gates, demanding regulation or nationalization. Ditto with water pipes and sewers – they’re just not safe investments given the governments they’re working with, so investors don’t make them. And even multifamily structures are tenuous, since, if regularized, they might have to comply with rent controls (which I hear are very popular in India, at least), making the initial investment less attractive.

Furthermore, there’s the issue of corruption, which would not be present in a true free market. The Guardian says of Cairo, “satellite cities […] mushroomed on the back of dirt-cheap land sales by the state,” and the New York Times cites critics as saying that “graft and corruption are widespread” in India. But crony capitalism is not the same thing as capitalism, even though leftists often like to equate the two. The Guardian, for example, blames Cairo’s slums’ huge wealth disparities on “the retreat of central government,” but this is directly contradicted by its earlier assertion that the wealthy benefit from underpriced land sales.

Anyway, I guess my point is that while gawking at slums and saying, “Look! The free market sucks!” might be a fun and easy game, it’s not very helpful. Slums might appear lawless to outside observers, but the hand of government and specter of its return are real concerns for its inhabitants and entrepreneurs, who shape their actions and investments accordingly.

Personally when I read the article about Gurgaon, my reaction wasn’t “Hey look how much this lawless place sucks!”, but rather, “Hey, look how much more awesome this place is than its neighbor!”

And by that I mean that they have jobs. Why else would people flock to a city that has no real infrastructure?

I think the moral of the entire story is that government has a quality multiplier…it multiplies prosperity in the direction of its quality…but sometimes that quality is negative. In those cases, it might actually be more beneficial (jobs!!!) for there to be no government.

I agree with Danny below–dysfunctional government is almost always a bad thing, but not all governments are dysfunctional. You accuse “leftists” of confusing capitalism with crony capitalism, but implicitly make the same error with regard to governments. Pretty much everyone agrees that Indian governance is bad, and often uses its authority to arbitrarily extract rents from random businesses. What this has to with governments elsewhere, I’m not entirely sure.

And the statement “there’s the issue of corruption, which would not be present in a true free market”, is nonsensical. Either you’re defining “corruption” such that it requires government to occur–in which case I would suggest your definition is non-operational–or it’s a false statement. Corruption grand and petty is routinely found in the private sector; businessmen routinely, given their druthers, will try to purchase defection (espionage, sabotage) amongst their competitors’ employees; salesmen will often attempt to win business with kickbacks to customers’ purchasing agents and managers, and there are plenty of cable installers out there willing to provide “free” services to homeowners for a small fee on the side. There would be far much more of this, certainly, weren’t there a government which actively prosecuted such breaches of good faith and fair dealing.

Your acknowledgment of “crony capitalism” makes clear that capitalists are perfectly capable of corrupt behavior; but any serious examination of the subject reveals that they can do so without the state’s participation.

What I saw from reading Robert Neuwrith’s book on the subject is that the slums (at least the better-off ones, especially Rocinha) epitomize anarchism rather than capitalism. They do not have much of either government or large-scale capitalism, and for the most part are not worse off for it. Infrastructure is the main exception: more-or-less self-governing communities can police themselves and create wealth, but not build rapid transit or large power plants or water works of the class that sustains New York.

Another aspect of this that indicates anarchism rather than capitalism is that the model of property isn’t like what we’re used to in the legal world. Neuwirth comes down pretty hard on de Soto’s regularization proposal: for one, what to do about squatters who rent from other squatters, or build a one-story building and then sell air rights above it to another squatter? But more fundamentally, the local doctrine in such areas is of possession rather than property. Indeed the community views absent landlords with scorn – especially people who keep properties vacant so that they can rent them to tourists during Carnival for much higher than regular rent but still lower than hotel fare.

But it’s lazy to equate them with the free market

Allow me to commit heresy.

I doubt the existence of the entity that is called “the free market.” To me, this term is theologically loaded.

Use of the word “the” implies a single agent, one that might be capable of imposing divine judgment or will. That seems to be the case when you hear someone say “Let the free market decide.” Isn’t that a plea for divine intervention, as though we as individual actors are incapable of acting and taking credit or blame for our actions?

“Free” implies that any and all encumbrances are automatically bad and harm economic activity. For most of history, we have had to make economic decisions with so many bounds placed upon us that free is often just the conditions that are the opposite of the ones were living in. And societies have been able to make economic arrangements in less free or unfree conditions. Think of gift societies, communitarian kinship bonds or ascetic groups for whom economic gain is secondary to personal self-discipline or group duty.

Even “market” can be flexible in its meaning. Many societies can form alternative means of exchange and accumulation, and incompatible market systems are flexible enough to offer some integration. The capitalist U.S. can trade with communist China and Vietnam, and there are some alternative economic development regimes that show more promise (microfinance and migration-based remittance flows) than capital-intensive and heavily planned rural development.

Maybe “the free market” is a set of small, random actions that people carry out in their lives and make up as they go along, and it gives the appearance of an organized, unified whole.

michael kors outlet online

Some notes on slums and free markets | Market Urbanism

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here: marketurbanism.com/2011/06/12/some-notes-on-slums-and-free-markets/ […]

michael kors bags outlet

Some notes on slums and free markets