David Block-Schachter. Image source: Bridj

Public transportation service provision is changing. As I already have mentioned in this post at Caos Planejado, microtransit services are growing in many cities around the world and one of the forefront companies on this field is Bridj, operating in Boston since June 2014 and Washington DC since May 2015.

I had the opportunity to interview David Block-Schachter, Chief Scientist of Bridj at Bridj’s office in Boston last October. Check it out:

Marcos Paulo Schlickmann: Could you tell a little about yourself and your inspiration to work in this field?

David Block-Schachter: About 8 years after finishing my bachelor’s I went back to school to do a PhD in transportation at MIT. After the PhD I worked for the MBTA as their Director of Research and Analysis to understand how they can use their data to improve operations. After that I joined Bridj. We wanted to improve mass transit generally, and looked at the issues here in Boston as our first focus. And obviously my background helped too. We also looked at informal transit systems all around the world. When I went to Rio I noticed how the buses are at a disadvantage, because the traffic itself is so unreliable that if you have a car you would prefer to be stuck on traffic in your car than in the bus. So we asked ourselves: “How can we use technology to combine the direct service associated with small vehicles with the good level of service we see in mass transit systems in America and Europe without inheriting the defaults and drawbacks of each system?” And the main advantage of direct trips instead of changing vehicles can be addressed by technology.

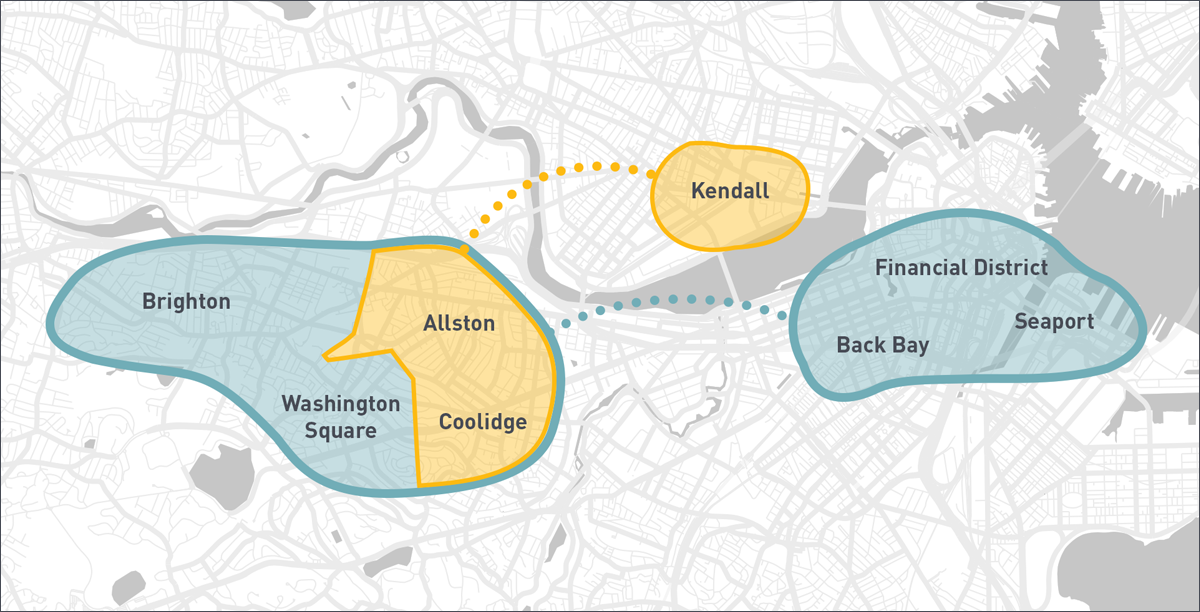

MPS: As we see on the map depicting Bridj’s service areas, the company runs buses in 3 main areas with two main lines: Allston/Coolidge Corner to Kendall/MIT and Brighton/Washington Square (including Allston/Coolidge Corner) to Boston CBD. How did you come up with those routes and service areas?

DBS: To come up with the lines we used a mix of art and science. Some intuition combined with data (demand data, MBTA network) and optimization algorithms. In our model all trips must be pre-booked through the Bridj App, so we have plenty of data and can keep track of our quality indicators. Passengers input their origin and destination and our software then calculates the walking time to and from the nearest stop. So one of our main quality indicators is walking time. Because commuting is about routine, reduction in walking times are constrained by a bias toward consistency, so we don’t change stops and routes “everyday”. The stops are defined in advance but are modified regularly according to the data.

Bridj service area

MPS: How do you see your competition? Is the private car your main competitor?

DBS: We see Bridj as a complementary service to “technology transport systems” – mobility services such as the Hubway system and Uber – that can improve city mobility and the environment as well. Some costumers take Bridj every day; some take when is raining; and some see Bridj as a “special treatment” when they don’t want to go by subway or bus but don’t want to pay as much as a taxi ride. Bridj is cheaper than Uber/taxi, quicker and more comfortable than existing public buses and has a sense of reliability for the passenger. But yes, we are all competing mainly against the private automobile.

MPS: As you may know, in South America and Africa the main feature politicians and the general public dislike about private transit is the so-called “Penny War” or “Guerra del Centavo”, meaning a bunch of minibuses running down an avenue competing for passengers. However this is not the case for Bridj. First, because you don’t have competition for now (i.e. another Bridj-like company), and second, you pre-book all trips. How do you see this broad subject of Competition on the market instead of for the market?

DBS: As I see there’s a cycle of regulation and government intervention: the government sees a city with the minibuses and all the on-street competition, starts “routinizing” and regulating the market, vested interests appear, the service degrades, government starts allowing some privatization here and there and finally they deregulate again and so on. But I think there’s room for “melding in the middle”. Not totally deregulated but also not totally public-owned systems. Through the use of technology you can get rid of a lot of the bad competition in the market. Basically if government forbids on-street competition, meaning all trips must be pre-booked, you get rid of the incentive to compete on-street. That way you can get rid of the negative effects, mainly safety issues, from such reckless behavior. Technology can help address in-vehicle safety and security issues too: bad drivers, unclean vehicles, women being harassed, etc. For example, vehicle tracking and passenger loads can all be addressed with technology. This, for the regulator, means you know where the vehicles are, who is in each vehicle, and who is driving. So, in a bigger picture, Bridj can be a platform that many operators can use to sell their trips and also the government can keep track of the market. In that way you can keep the advantage of having entrepreneurs with their small vehicles and direct services available for the whole community.

MPS: Do you own the vehicles? What about the drivers?

DBS: We don’t own the vehicles. We have contracts with vendors and driver partners. Approximately 30% of our fleet is unbranded but we’re constantly trying to get to 100%. The best marketing is the branded vehicles. Our Ideal vehicle is between 12 and 15 seats. According to our data and experience this is the perfect size to ensure the right balance between stops and speed to the destination. So the vehicles fill it up at a good pace and don’t need to stop so much.

MPS: What about regulation? Did you face strong opposition from the establishment as Uber and other TNC and microtransit companies in the US and around the World?

DBS: We started about a year ago and I thought the regulatory issue would be the most significant one and was a little frightened at first but what we found is: If you go to the regulators with good intentions they respond well. We’ve had very few hiccups along the way. And it is important to have good relations with municipal governments, the State, the Governor’s office, and in general public bodies and authorities. For the size of our operation, we’ve talked with a significant number of government agencies. It is important to highlight that they want us to operate and not the other way around. Unlike companies like Uber we don’t have the “establishment” against us; we’re not fighting intrinsic interests of taxis. In our case even the public transit agencies like us, there’s so much demand for mass transit! Especially in Boston where we provide a relief for areas with overcrowded or underserved public transit services. We’re increasing transit capacity at those places at no cost to the agency by giving more options for population and increasing accessibility. And we have very good relations with the towns and cities we run our service. We’ve been proactive, we’ve reached out to them and said: Let’s talk about ways we can work together. Although I have to add we learnt a lot from residents and neighbors in Brookline. We started with larger vehicles as they were easy to obtain from the vendors compared to the smaller ones. Those vehicles were noisy, took a lot of space and residents complained. The vehicles now are different: Small, clean and quiet. They don’t disturb the neighborhood. The neighbors really helped improve our service.

MPS: How can I become a Bridj customer? How does the system work for the user and when?

DBS: For now we’re operating in Boston and Washington DC. We operate just peak services; but it will change over time because we know the demand patterns. The user downloads the Bridj App. She then must input her origin and destination in the App and a couple of trips are offered for different times and prices. We use a price mechanism (I.e. higher prices on higher demand) in order to make sure that, as much as possible, there is always a seat. During the peak of the peak the prices are higher but it’s not surge pricing. We want to avoid trips that are sold out. When trips are sold out and vehicles are evenly distributed over time the passenger has to wait more for the next trip so it feels that the system provides lower frequency. Our target is to always have one seat free, which means that vehicle can be booked. The great advantage is because we have new demand data every day we can see where we can adapt, where and when we have over and under supply.

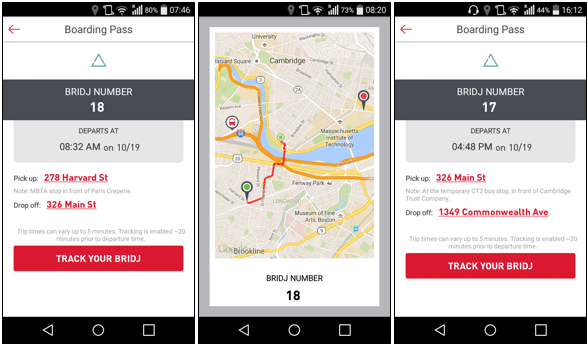

Trip I made with Bridj: the “boarding pass” I had to show the driver and the map to track the vehicle.

MPS: What about the future?

DBS: I see that the future of mass transit is using technology to augment buses, trains and infrastructure. I believe autonomous vehicles will revolutionize mass transit. It’s going to happen. There’s a big question of when and how, but it’s going to happen. And the question is: will those vehicles be single or multi-occupancy vehicles? Mass transit agencies have been running autonomous vehicles for 50 years but they are falling behind in it. And as public agencies they have right-of-way and established routes and stops, autonomous vehicles would work pretty well for them. And Bridj also hopes, in the future, to incorporate autonomous vehicles in its operations. For Boston I can imagine a bus system that just uses Bridj technology.

Great interview!

I read Jarret Walker’s Human Transit and found it excellent, but it’s interesting how the experience of Bridj and other microtransit providers differs from Walker’s claim that smaller buses don’t pencil out, because labor costs are so high.

Is it that most Western transit systems use expensive union drivers and mechanics?

Smaller buses are better because they are quieter and more frequent, and cause less wear and tear on the road. And are probably easier to source and modify. It’s exciting to see how markets can compete with the ease and cost of the private car, with the convergence of technology, density, and open minded governance.

Question to David Block-Schachter: What class DOT license do you (or your contractors) require your operators to hold?

The small size of your vehicles suggests that in comparison to a transit bus, who need a Class B license (>8 [when carried for profit] passengers, >26,000 lb GVR) with passenger endorsement and no air brake restriction, you only need to train your operators to get the lesser Class C (no passenger restriction, but no vehicle >26,000 lb GVR), with air brake restriction.

Often, it is assumed that if the transit company uses smaller buses, they can pay their operators at a lower wage class, as they are only trained to operate minibuses, not full buses. The reality is that the difference between Class C with an air brake restriction and Class B licenses without the air brake restriction, which regulate which type of bus the operator can drive, is a few extra minutes at the DOT taking a different test plus the air brake test, and road testing in a slightly larger vehicle with air brakes. The short term cost, for both the transit company and employee, is so low compared to the long term wage gain for the operator and scheduling flexibility (ex: Bob called in sick for his transit bus shift, so can you the minibus driver spare some overtime to drive his route after your shift?) that the transit company gains.

So running a bigger bus makes more sense for private transit providers as well? The bigger bus would also reduce frequency.

Incidentally, I wonder if, to the extent that there is a cost advantage to bigger buses, how much of it is eroded once you account for the damage of big buses to the roads.